Here are two articles I wrote for Worldradio in the 1990s about events in the 1980s-90s. The first is about a neighbor experimenting with radios in the 1910s, the second is about my experience getting a reciprocal license in Venezuela in 1985, and the last article is about a sailboat delivery that went awry. A little sliver of history...

Getting on the air in Venezuela Worldradio, August 1995 [recalling my time in Venezuela in 1985]

Fresh coffee was handed to me as I

settled into one of the waiting room's tan leather chairs. I eagerly accepted

the delicious brew and was ready to wait a long time to see the Venezuelan

official who would give me my reciprocal ham license. I had just finished

panning across the walls of windows that revealed the bright green mountains

which encircle Caracas when I was introduced to the radio licensing manager.

With a friendly handshake he led me to his office. Fresh coffee was brought in

and we were ready to conduct business Venezuelan style.

I was managing an oil exploration crew

in southern Venezuela and while in Caracas on my leave from the crew, I got

into an ancient Chevrolet with foot-thick doors and made my way to the radio

communication office to get my YV2 call. I had worked with Venezuelan

officialdom in my job with mixed results. Although "collaboration"

fees are required by some petty officials in Venezuela, generally they have a

wonderful style of business. It starts with warm hospitality and evolves into

learning the nature and disposition of their guest. The introductory chit-chat

lasts much longer than in the U.S. and a cordial atmosphere is quickly

developed as you debate whether to invite your new friend over for Christmas.

Back in the radio office we finally got

to business. I quickly got my license certificate and the radio licensing

manager even paid for the fancy stamps that made it all legal.

Continuing our conversation, he tells me

about some other "American radio people" from the U.S. He introduces

me to them and it turns out they were with the U.S. Department of Commerce and

were working on spectrum management. They were not too impressed at meeting an

expatriate ham.

In trying to involve myself with the Venezuelan

ham community—which I would not be able to do in my remote camp—I visited the

Caracas ham radio club. There I was warmly greeted by the well-dressed crowd.

Their "International Chairman," who spoke excellent English,

immediately befriended me. We were seated in the front row and watched the

whole proceeding. At the end of the meeting, new officers were installed. This

procedure included the officers raising their hands as they took an oath to

comply with their assigned duties. A very formal and serious approach to ham

radio indeed.

After the meeting, I was given a tour of

the club station which consisted of the best Collins equipment available. I

left my newfound friends, once again appreciating the fraternity of ham radio

community and the wonderful state of ham radio in Venezuela.

Interpreting Silence Worldradio, March 1990 [Recalling my sailboat delivery in 1988]

The engine didn't work, the batteries

were nearly dead and we had 15 days of cold North Atlantic sailing to go.

"How much radio time do you

think we have?"

"I'd estimate 10 minutes of

transmit time on sideband. "

An unfortunate but wholly prudent

decision was agreed upon.

The job was to deliver a 38 ft.

sailboat, the Ishmael, from Cape May, NJ, to Falmouth, England. Onboard the

delivery were the owner, a professional skipper, myself and another crew

member.

All but the skipper were volunteers but

we all had our own reasons for participating on this trip. In addition to the

charm of arriving in Europe by sea, I was motivated by a desire to further my

ocean sailing experience and to visit with family and friends in Norway.

The boat was a nine-year-old sloop

equipped with the requisite equipment for a transatlantic passage, including a 100W

channelized, general coverage SSB transceiver. And that, of course, meant that

ham radio was coming along!

Although I am not a particularly active

ham, there have been occasions when I have pulled out the old ticket, blown the

dust off it and had it serve me well.

With the help of Vince West, W90PY, and

Jay Gooch, W9YRV, we set up a program to monitor the boat's passage and to

handle messages. Vince (living in Illinois) set up several relay stations in

strategically located areas. Most helpful were G0DOD in northern England and VO1CA

in Newfoundland, Canada.

Vince and I went over the radio system

so he was familiar with what we had to work with. The radio system, including

spares, included: One ICOM M700, general coverage SSB transceiver; one

automatic antenna tuner; three deep cycle batteries; two alternators and one four-cylinder,

Perkins diesel engine. The primary antenna was the backstay, which is the

supporting cable that extends from the top of the mast to the back of the boat.

The backstay was insulated at both ends

and attached to the antenna tuner by means of the center conductor of a RG-58

cable spliced into the stainless-steel stay. The stay was oriented at a about a

70-degree angle to the horizon and this nearly vertical orientation with the

Atlantic Ocean as a ground plane, provided a good antenna system for such a

small space.

The backup antenna had to be strong

enough to handle storm conditions, yet be compact enough to store easily.

Moreover, the antenna had to be small enough to rig on a 38 ft. sailboat.

The compromise was met by the venerable

dipole cut for 15M and made of a stranded phospor-bronze wire that Jay had

saved from one of his far-flung radio tests. With heavy duty insulators, RG-58

feedline and lots of silicone, the antenna rolled up into a nice, small ring.

In addition to the SSB, the boat had a

VHF-FM, marine band transceiver and an Emergency Position Indicating Radio

Beacon. The EPIRB transmits a beacon on the aircraft distress frequencies of

121.5 and 243.0 MHz (they will soon be able to work on the satellite monitored

frequency of 406.025 MHz also).

All the large metal parts of the boat

were electrically attached and grounded to the lead keel. This system provides

a fine RF ground — especially in salt water. If this ground had been

inadequate, we had available the lifelines that go around the boat, which could

have been fashioned into a counterpoise.

Vince and I set up primary and backup

frequencies, as well as the names of relatives in case we used AT&T's High

Seas service to call a relative and wanted to coordinate that information.

We embarked on our trip on a warm, sunny

day in May and headed out to sea with the eagerness of sled dogs. On the first

day the weather quickly went from T-shirts to sweaters and fog descended upon

us. All this, even before we were out of sight of land.

We established a watch schedule based on

a two hour on, six hour off, pattern, giving us each three watches per day.

The days slid by quickly, getting

continually colder as we sailed north by northeast. Even the warm waters of the

Gulf Stream didn't seem to resurrect that moment of summer we had aboard when

we first embarked.

I was amazed at how much wildlife there

was to see. Every day I would see something: Birds, porpoises and even whales.

I was most impressed with a small black and white gull that looked a lot like a

sparrow. This bird would venture out into any kind of frigid sea, swooping into

the deepest troughs, searching for some unfortunate, edible thing. I never saw

them catch anything, but their game of ocean-tag must have been entertaining

sailors for centuries.

On our sixth day, as we moved with the

Gulf Stream, we arrived at a unique waves place called the Grand Banks. This is

one of the richest fishing grounds in the world. The ocean floor rises to less

than a 200 ft. depth and the Labrador Current, originating from cold polar

waters, just begins to engage the Gulf Stream in its losing battle.

Although the Labrador is not allowed to

venture far from the Canadian coastline, its interaction with the Gulf in this

shallow water creates a rich environment for marine growth. I saw ocean going

trawlers every day in this area, leaving a trail of dead fish in their wake.

The seascape took a different form here

too. The odd combination of waves produced a sea that reminded me of the

rolling hills of northwester Illinois. Sometimes the waves were quite steep and

the boat would surf down them with water foaming and boiling around the hull.

Daily life had fallen into a slow speed

routing; sleeping, eating, steering, fixing things and then sleeping again. The

sleeping always seemed to be in short supply; even though I had a lot of “free”

time it was hard getting used to

waking up at 2 a.m. to stand in wet,

freezing air for two hours. The two hour watches in cold weather and sometimes

stressful sailing conditions really took a lot of energy. We ate well, however,

as the boat was stocked with good food and everyone except me was talented in

its preparation.

The sked with Vince, Jay and the gang

went well. Every other day I would call in and was greeted by familiar voices.

Propagation to Illinois wasn't too good, but it was passable. Contact with VO1CA

was impossible on 20M and the backstay was too short to load well on bands

below 20M.

However, G0DOD's voice boomed in on both

20 and 15M, with a calmness and gentility that provided a refreshing contrast

to our wet, sloshing environment. Unfortunately, because we didn't have a lot

of diesel fuel available for battery charging, I couldn't do much ragchewing;

just a hello, our position, bearing, speed, weather and overall condition. The

Maritime Mobile Net was also very helpful, although our tiny signal was

sometimes not heard.

As we passed the Grand Banks, our

environment became dominated by sounds and coldness. The boat made sounds as it

worked through the seas. The waves made sounds; the wind, rigging, and even the

coldness itself contributed to the cacophony of nautical serenity.

Only on one occasion, when the boat was

drifting under a light wind, was the sound changed. Three curious porpoises

circled the boat for 10 minutes, blowing air and contributing the beautiful

sound of living pipe organs to the stillness.

Once a day we would intrude our

mechanical noise-maker into our simple life. Around 10 a.m. every morning we

would run the diesel for an hour or two to charge up the batteries.

On the eleventh day of the trip the

diesel did not start. The batteries were already low and the repeated cranking

produced no results. We finally found that a Thermos bottle had fallen over,

hit and opened a pet cock on the primary filter in the diesel fuel line causing

all the fuel to run out of the engine. I was able to use the lift pump to prime

fuel all the way to the pump, but I could not get it to flow the injectors.

We cranked a bit more to prime the

injectors, but with no luck. Given this unfortunate condition I assessed how

much battery charge remained and guessed that we had 10 minutes of transmit

time left on SSB. We quickly decided that we would give up on the engine and

save our batteries for emergency use only.

We took the additional measure of

disconnecting the terminals of one of the batteries to assure it did not leak

through the electrical system.

However, with the deep concern for

battery reserves, it was also evident that we should not even make one last

transmission on our regular sked to inform Vince and the relays of our

condition. When out at sea you have to be very careful in considering

contingencies and it is better to have worried friends than to be one second

short on transmit time when your life may depend on it.

Vince knew that we only had one engine

(and one radio) so he would be able to figure out that we had lost one or the

other. On the other hand, he could have also thought that we had lost the boat

and our EPIRB — an equally valid assumption.

All I could do was try to think through

how Vince would interpret this unplanned silence — an interesting mental

exercise. I thought that Vince would be able to figure out that there had been

no storms or unusual sea conditions in our area and he also knew that the boat

and the crew were in good shape as of our last sked, only two days prior.

We proceeded on to England with a

self-imposed power blackout: No radios, radio navigation (LORAN), freezer,

lights or autopilot (which was not working well in these seas anyhow). The

weather on this trip had generally been bad, meaning we had overcast days and

nights which limited our celestial navigation abilities.

Since the fastest way to England is via

the Gulf Stream, which corresponds nicely with the great circle route, we were

actually close enough to Canada during the first part of the trip to pick up

their LF LORAN signals. We would be able to pick up LORAN chains from Iceland

and England as we progressed eastwards.

With our batteries in storage, we would

need to rely on celestial navigation and therefore be subject to the whims of

the clouds.

The day the engine had failed to start

was a relatively calm one. However, the next day the winds shifted so that we

were going into the wind and the waves. This slowed us down because we lost

some of our sail power and had additional hull resistance from the ramming of

the bow into the waves.

The second day after the engine failure,

we noticed sea water seeping into the boat through the bow. Each time we would

bang into a wave, water would ooze through the inside mat of the fiberglass

hull. We quickly cleared the bow section of all the wet odds and ends that were

stored there, making a terrible mess of the boat in the process, in order to

find from where the leak was coming.

The water was coming through the fiberglass

in a 1 X 2 ft. section of the bow. The amount of seepage would increase

substantially when we hit the waves, but we could not find any single source of

the leaking.

The amount of seepage was very small,

well within the capabilities of our bilge pump, but what was happening to the

hull? Was there a small crack in the hull? Was the nine-year-old fiberglass

delaminating?

With the boat banging into each wave and

spray flying over the bow, it was impossible to check the outside of the hull

at the bow. It seemed that no matter what was causing the leak it was possible

that it could get much worse.

We put the EPIRB and some food and water

into bags and attached them to life preservers and set them out in the cockpit.

Our choices were to continue on to England, which would involve 10 days or so

of battering seas, or to head to the nearest point of land and assess the

boat's condition there. We decided to head to land, once again a pretty easy

choice.

The closest land was Newfoundland,

Canada. It was less than 200 miles west. We turned the boat around and headed

for it.

It took two days to get to Newfoundland,

and the sight of the barren land on the horizon provided a mixed welcome. We

sailed into St. Johns Harbor and, while docking under sail, smashed the bow

into the concrete wharf—the solid feel of land.

We put in fresh batteries and were able

to easily start the engine. Could we have done that with ours? Who knows?

After five days of radio silence, I

turned on the radio and heard Vince talking about me. They were not sure what

had happened to us. I jumped in to tell them that we were all right and in St.

Johns. Much to my dismay, a well-intended but confused ham who had heard their

repeated calling for me said that he thought he had heard me two days prior! A

bad and possibly dangerous mistake.

Because ham radio was the only way we

were communicating with anyone, we relied on its accuracy. If we were in

danger, surely no news would have been more helpful than false news.

Fortunately, Vince had seen through  it all, discounting the

erroneous report and assuming we had radio trouble. In his concern, however, he

had recruited several big guns to call and listen for us.

it all, discounting the

erroneous report and assuming we had radio trouble. In his concern, however, he

had recruited several big guns to call and listen for us.

When we arrived, one of the crew  members went home, having lost

confidence in the boat, and the owner

members went home, having lost

confidence in the boat, and the owner  decided that he didn't want to

continue

decided that he didn't want to

continue  to England.

to England.

Upon inspection, it turned out that the

leak was caused by a separation of  the anchor well bulkhead from

the

the anchor well bulkhead from

the  deck. After repairing the boat

as best we could the three of us tried to sail it down to Sydney, Nova Scotia,

but were

deck. After repairing the boat

as best we could the three of us tried to sail it down to Sydney, Nova Scotia,

but were  turned back by adverse wind.

turned back by adverse wind.

The boat was finally berthed in

Conception Bay (a days sail northwest of  St. Johns) and I flew to Norway

to get a short vacation out of the trip anyway.

St. Johns) and I flew to Norway

to get a short vacation out of the trip anyway.

/ tom-ask-479096822

Here is an earlier discussion of AI and music:

/ tom-ask-479096822

Here is an earlier discussion of AI and music:

![]() • Song vs poetry - and a new remix!

AI and personal style:

• Song vs poetry - and a new remix!

AI and personal style:

![]() • Style versus AI

AI and ideation:

• Style versus AI

AI and ideation:

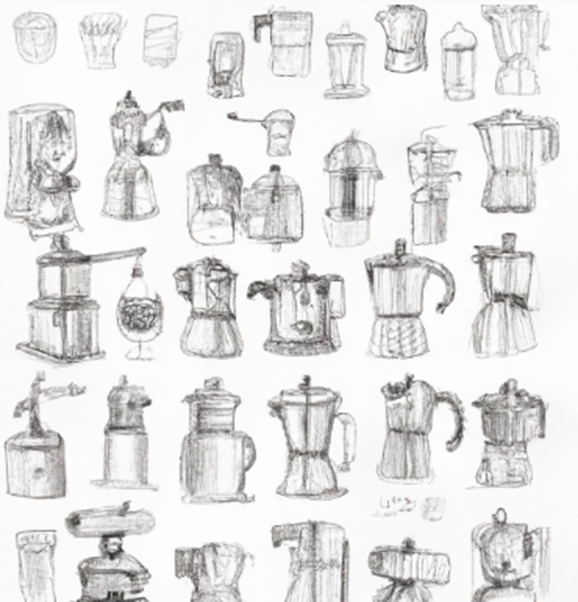

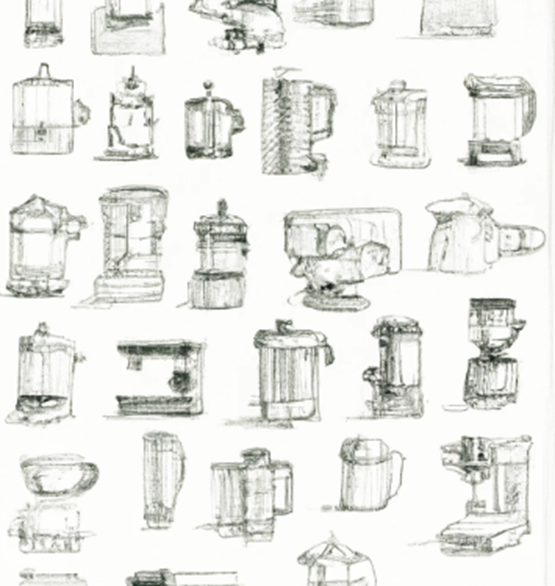

![]() • Death of Ideation Sketches

• Death of Ideation Sketches