This was previously published by the Design for All Institute of India

Steps toward integrative palliative

care in the developing world

Thomas Ask, John Boll, Alexander Nesbitt

Abstract

Treatment for suffering in low resource areas can benefit from easy access to medicines that treat pain, gasping, terminal secretions, nausea, anxiety, and delirium. Because suffering needs to be contextualized within prevailing cultural forces, individuals with communal connections with the patients must be empowered to administer these medications and provide caregiving services.

Additionally, developing low cost

medical dispensing systems allows a wider range of treatment. Artificial intelligence can be coupled to

voice recognition for both patient diagnosis and medical products to improve

efficacy of treatment.

Design can address complex problems through inquiry, synthesis and

creative exploration. Problems that lie

outside mechanistic solutions are fertile areas for design processes that

strive to creatively motivate improvements.

Improving healthcare is a type of problem that challenges deductive

logic and benefits from ‘design thinking’.

This inquiry recognizes the resource driven model of healthcare has

overwhelmed the relational needs required for palliative patient care. This article wishes to extend the medical

discourse beyond the well understood effects of disease and the positivistic

validations of pharmacology. While it is

presumptuous for those steeped in US medical traditions to assert appropriate

systems of palliative care in the developing world, this reflection on

palliative treatment intends to offer a different perspective that appropriate

local decision makers may find helpful.

Palliative care can consider three tracks: medical, relational and

spiritual. The medical realm can include

adjuncts to pharmaceuticals while the relational can cover areas of concern

ranging from the relationship between caregiver and patient to the effect of patient

pain and psychosis on family members. The

spiritual realm addresses deeply held beliefs about the patient’s relationship

to a deity in their faith tradition.

Background

Reducing suffering requires identifying a cultural framework that

connects pain and suffering. The

acceptance of pain and the expectations of palliative care requires a

subjectivist, interpretive epistemology. This epistemology draws upon the

humanist arguments against exclusive positivistic approaches that highlight

limitations of the scientific method and its inappropriateness for assessing

human thought and actions (Feyerabend 1993).

A theoretical

construct for understating the relational component of palliative care, beyond

pharmaceutical approaches, lies with the integration of psychological and

sociological theories. The identity theories, along with the phenomenological

perspective of an ideal self, suggest that when people identify as part of a

group they will deeply nurture each other’s attributes that tend to maintain

the group identity. Motivation for the

cooperative exercise of caretaking can be founded on the development of an

identity associated with a group. The identity theory asserts that one’s self-esteem

is derived from the identity developed from social interactions. The sense of

self is based on the roles that one assumes in a society or group with which

one identifies (West 2014, Stets and

Burke 2000). A shared group identity

can promote a desire to protect against those in other groups.

Pain is shaped by culture into a question

that can be expressed in words, cries, and gestures, which are often recognized

as desperate attempts to share the utter confused loneliness in which pain is

experienced (Illich 1976, p. 140).

Reducing pain and suffering is more

complex than medicinal treatment.

Addressing palliation requires deference to cultural motivators, self-identity

and other powerful, foundational forces.

An effective system for palliative care moves beyond medicine and includes

encouragement of relationally-rooted interaction between the patient and

caregiver as well as spiritual nurturing. The caregiver’s personal connection

with the patient is a key factor in reducing patient anxiety and maintaining

patient dignity. This caregiver relationship

is especially important for terminally ill patients. The medical treatment considers medication appropriate

for treating pain, gasping, terminal secretions, nausea, anxiety, and delirium.

Clinical pain in the developing world

Pain is the most commonly feared symptom

listed by individuals contemplating their eventual terminal illness and death. Unfortunately,

throughout much of the developing world, this fear is realized daily by

hundreds of thousands of people. The World Health Organization estimates that

more than 30 million people each year are in need of care to support them and

palliate their symptoms during their terminal illness, but the vast majority

cannot get this care. Millions suffer from untreated pain annually. This includes more than 5.5 million who die

from cancer and more than one million from end stage AIDS (NGO 2011). Opioids are one essential class of medication

to treat such pain, but access to these medications is very limited in much of

the developing world. Efforts to improve appropriate access to this class of

medications is an important part of the worldwide palliative care movement.

In addition, increasing access to non-opioid medications and non-medication

analgesic measures is also an important component in the effort to reduce

worldwide suffering in the sick and terminally ill.

Comfort kit

In established palliative care systems,

providing patients with an emergency symptom kit (or 'comfort kit') is a

routine component of preparing for the common forms of suffering which afflict

humans contending with advanced illness. The most common such symptoms are

pain, dyspnea (air hunger), nausea and vomiting, delirium (an acute confusional

state) and anxiety. Medications that are commonly included to treat these

symptoms include non-opioid pain medications (such as paracetamol or diclofenac),

anti-anxiety medication (such as lorazepam or diazepam), anti-emetic (vomiting)

medications (such as prochlorperazine), and anti-psychotic medications (such as

haloperidol). Some such packs also include anticholinergic medications to treat

the terminal secretions ('the death rattle') that often accompanies the

terminal state. Provision of a comfort kit including these inexpensive

medications alone, or even better, including simple commonly needed care items

such as simple dressings, a urinal, and perhaps antibiotic ointment, would

greatly enhance the comfort and the dignity for those who are ill and

suffering.

Interpersonal relations

Medical practitioners typically enroll medications to ameliorate acute

symptoms. However, the notion of pain is

contextual and culturally moderated.

Therefore, palliative care must rely most deeply upon the personal

relationship between the caregiver and patient.

The patient must conclude that the caregiver understands the patient’s

suffering. The caregiver must ask the

question, “What would you most like me to know about you so that I can take

care of you?” This inquiry is easy to

present in the abstract but the patient – caregiver relationship is an

entanglement comprised of a web of values, history, social norms, and

regulatory requirements.

A caregiver will never fully understand their patient’s suffering but

must rely upon a deeply held sense of personal responsibility in treating and

comforting the patient. This type of

relationship is more naturally derived from family relationships than from the

medical community. In addition, the patient’s

expectations can motivate the approach to palliation. Consequently, the

attending physician must understand:

- ·

Social and

cultural norms.

- ·

Pain is contextual

and subjective.

- ·

Patient recognizes

not all suffering will be lifted.

- ·

Relationship

between patient and caregivers.

- ·

Effect of illness

on family.

Spiritual

Faith traditions are important in contextualizing suffering and identifying a purpose to pain. Given that the experience of suffering frequently challenges the core of an individual such faith traditions can be an important aspect of providing care both to the patient and their family. Through the values and meaning in a faith tradition suffering can represent a means to develop character and hope in the midst of an illness. Alternatively, patients can believe the purpose of their pain is for discipline or correction or an indiscernible purpose but still governed by their deity. Therefore, addressing the spiritual can be an important part of palliation and subsequent comfort for the suffering individual.

Artificial intelligence (AI) can democratize access to patient

assessment and guide dispensation of medicine.

Computing systems incorporate AI, such as expert systems and artificial

neural networks, that strive to model human thought in a manner that can be

processed on a computer and accessed by a non-expert user. However, sharing human knowledge and

expertise is a difficult task. People

use very sophisticated and intricate thought processes to solve problems, recall

information, and make decisions.

Although expert systems are an excellent technology to save and

disseminate knowledge, transferring that knowledge from the domain expert to

the computer is difficult. Acquiring

knowledge for an expert system is the art of structuring human instincts,

experience, heuristics (“rules of thumb"), guesswork and all the other

words which never can quite explain the human thought process. Expert systems use fuzzy logic to make

decisions. That is, the confidence of an

output is quantified and that value can be handled separately from the

output. The confidence output is then

used in determining the best, final decision of the expert system. The combination of outputs and the confidence

associated with them adds intelligence to the system. In this way the “degree of truth” of

information can be managed.

Neural networks use a large number of processors with each

artificial neuron dedicated to a specific task.

The neural networks organize the links between inputs, outputs and

hidden intermediate layers of decision making.

Sensory or database information is fed through this network with each

neuron processing the data independently and progressing its results through

the network. Generally, a feed forward

approach is used where information flows from the input neurons, through the

intermediate neurons and finally to the output without a feedback mechanism. In this manner, large amounts of information are

processed to identify relationships and therefore create a dynamic algorithm

that can accurately develop conclusions from salient inputs.

Voice recognition is often coupled with AI allowing computing systems

to recognize natural language usage and discern emotion. AI driven voice recognition allows simplified

access to computing power. Currently

voice systems are more than 97 percent accurate in identifying individual words

and are being quickly implemented due to commercial interests (Brown 2016).

However, reliance upon AI driven voice recognition has potential

problems with error and abuse.

Systemic approaches

Improving the quality of life for people contending with the symptoms of

serious illness requires the care best offered through those who have a

personal connection to the patient. Medical

approaches typically involve a professional caregiving team who develop and

execute a plan of care (Ferris 2002). However, where

this resource intensive approach is not possible, a system of palliative care

requires altruistic volunteers to provide treatment and personal support for the

patient. These volunteers are educated and authorized to give support, evaluate

and treat using prescribed protocols.

The volunteers are given comfort kits through the medical

establishment. If a volunteer from a

family, community, or religious group is unable to provide care, a

paraprofessional would need to be engaged; however, this is not the optimal

arrangement because the altruism becomes distorted by financial forces.

The comfort kit would need to be issued specifically for one patient;

however, the comfort kits have value and therefore present potential for

misuse. The contents could be resold,

which is the most direct problem with the effective distribution of comfort kits. In addition to financial gain, the

distribution system provides power over the patient that could be misused. Additionally, administration of medicine could

be met by resistance within the medical establishment as well as social forces that

resist a lay person’s ability to dispense medicine. Control of medicine delivery could be

addressed by technical solutions such as time release containers, drone

deliveries or other ‘just in time’ systems.

However, these delivery systems are vulnerable to theft and abuse.

Caregiver training and adjuncts can improve suitability of

treatment. The caregiver adjuncts can

range from video supervision by a physician to cards with photographs and

corresponding treatment protocols. The

medical community must recognize untreated, acute pain can develop into chronic

pain. Therefore, aggressive treatment of

acute pain through opioid and other medicines is recommended so that chronic

pain will be reduced.

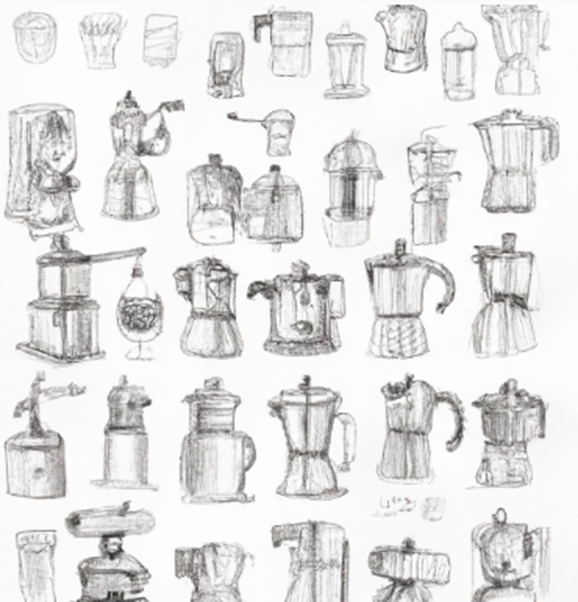

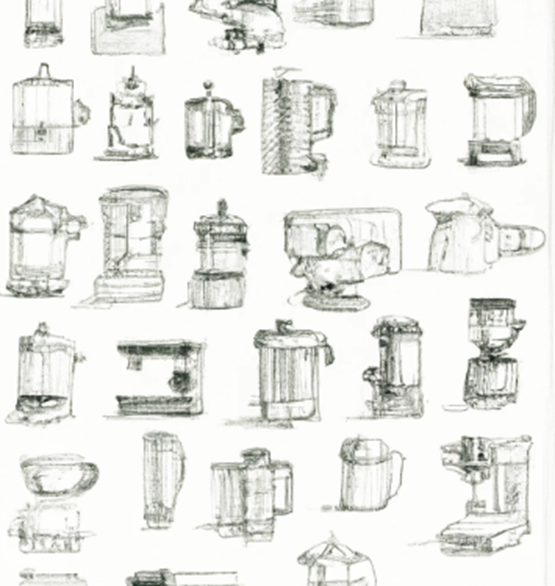

Future approaches

While relationships and spiritual connections will always be key

components of palliative care, mechanistic designs can provide helpful

improvements. These can range from AI

guided medicine dispensing systems to human powered refrigeration

compressors. In addition to AI guided

and remotely based medical supervision, advanced design approaches would call

for low cost/high impact devices. Some

technologies are seemingly difficult to develop such as systems that deter

opiate abuses and secure medicine distribution.

Improvements can be more product specific, such as refrigeration and fluid delivery systems. If patients have refrigeration available they can store and dispense a broader range of medications Appropriate technologies may include human powered refrigeration compressors, solid state thermoelectric refrigeration, high thermal mass systems, and minimized volume super-insulated storage systems. Low cost, easy to use fluid and drug delivery systems such as infusional subcutaneous and syringe driver systems would also aid treatment. Usage of medical products can be facilitated using AI driven voice recognition. Additionally, drone delivered medicine and radio and video communication allows treatment in remote areas.

Conclusion

Palliative care transcends medicine and technology. The spiritual and interpersonal relationships

infuse into patient care in forms that are difficult to characterize. However, in low resource or remote

populations the administration of medicine and care is best administered by

altruistic individuals such as those affiliated with the patient by family,

community or religion. These caregivers

need to be richly empowered to provide treatment necessary to address issues of

pain, dyspnea, nausea and

vomiting, delirium, and anxiety.

Comfort kits should be provided to these

caregivers that would include non-opiate pain killers such as paracetamol and

diclofenac. Other medications would

include paracetamol, diclofenac, lorazepam, diazepam, prochlorperazine, and

haloperidol. Other items such as

bandaging and a urinal would also be provided.

Within the realm of product and

systems designs, technical advances that allow remote monitoring and AI

guidance can provide improved diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, low cost versions of refrigeration

and drug delivery systems will aid in treatment options. Developing non-addictive pain medicines have

been largely unsuccessful; however, customizing pharmaceuticals such as abuse

deterrent opiates designed to genomically key to the individual could reduce

abuse.

Palliative care in the developing

world can be improved by empowering nonmedical personnel who are communally

connected with the patient. These

individuals can best answer the question, “What would you most like me to know about you so that I can take care

of you?”

References

Brown, A. (2016), Talk to Me. American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME)

Mechanical Engineering, No. 11, 138, Nov. 2016, pp. 32-37.

Ferris

FD, Balfour HM, Bowen K, Farley J, Hardwick M, Lamontagne C, Lundy M, Syme A,

West P. (2002), A Model to Guide Hospice

Palliative Care. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association.

Feyerabend, P. (1993), Against Method.

New York: Verso.

Illich, I. (1976), Medical Nemesis: The expropriation of health. Bantam Books/Random

House.

NGO Human Rights

Watch, (2011) [Online] Global State of

Pain Treatment-Access to Medicines and Palliative Care.

Stets, J. & Burke, P. (2000), Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory.

Social Psychology Quarterly 63,

2.

West, R. (2014), “Communities of innovation: Individual, group, and organizational characteristics leading to greater potential for innovation: A 2013 AECT Research & Theory Division Invited Paper.” TechTrends 58.5, (9), pp. 53-61.